Aphrodisias 1972: a memoir

Archaeologists rarely write about the conditions

of field research. What were the living conditions like? The rooms, the beds,

the bathrooms, the food? What was the work schedule? Was the atmosphere

congenial? Did the participants get along with each other? What about the

locals, who in the Near East so often are hired for the hard labor, on the one

hand, and for running the excavation house, on the other? Were they treated

with respect? Were they interested in the research?

Archaeologists conduct field work as part of

their research projects. After data is collected, the results must be

documented, analyzed, and published. This is the scientific aim of archaeology.

Without publication, excavations are simply destruction. It goes without

saying, therefore, that the attention and efforts of archaeologists are focused

on fulfilling these scientific goals. The chronicling of how a project is

organized to further these aims has, for the most part, never been considered

an essential part of the published record.

How do we

archaeologists, not to mention the public at large, know about how field

projects are organized? Personal experience is hugely important: by serving on

the staff of an excavation. After that, word of mouth: what fellow students and

colleagues tell you about their experiences at other projects. Beyond this

network, though, it’s almost impossible to learn what it was like to work on a

particular project. Notable exceptions have included Come, Tell Me How You Live, which Agatha Christie wrote about her

experiences on excavations in Syria in the 1930s. But not every archaeologist

has, like Max Mallowan, a spouse who is a famous, prolific writer. And Christie

was not herself an archaeologist, although she certainly helped out during her

husband’s excavations.

I myself have taken

part in 27 field seasons, mostly excavations, several study seasons, and one

surface survey. There is much to remember; there would be much to record. One

season that particularly sticks in my mind, perhaps because it took place at

the beginning of my career, but certainly because of its strangeness, was a

month spent at Aphrodisias in the summer of 1972.

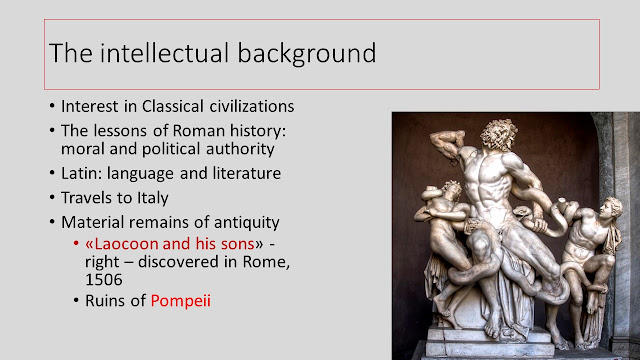

(Aphrodisias: Introduction. www.nyu.edu)

Aphrodisias, located

100 km inland from the Aegean coast in southwestern Asia Minor, today Turkey,

was inhabited from prehistoric times, but achieved particular prominence during

the Roman Empire, from the first century BC into the seventh century AD. After random explorations in the earlier 20th

century, excavations on a large scale began in 1961, under the direction of

Kenan Erim, a professor of classical archaeology at New York University.

The place is supremely beautiful. In 1972, when I worked there, the ruins were

a Romantic’s ideal: Roman architectural fragments scattered among trees and

bushes, with mountains in the distance.

(South Agora. The Friends of Aphrodisias Trust. www.aphrodisias.org.uk)

The small village of Geyre still

occupied a good portion of the ancient site. Little by little, the villagers

were displaced to a new location off the ancient site; their houses were

demolished, to allow excavation to proceed unhindered.

In

addition, the site was already known, even before 1961, as a prolific producer

of high quality sculpture, profiting from nearby marble quarries. Nearly 60

years of excavations have confirmed the scientific promise of Aphrodisias: the

architecture, the sculpture, the evidence for city development, the finds have

all yielded a vivid picture of ancient life in this city.

I happened to join the

1972 staff by accident. Machteld

Mellink, the distinguished specialist in Anatolian archaeology and professor at

Bryn Mawr College, was interested in the prehistoric remains from Aphrodisias.

They could potentially contribute much to our understanding of the Aegean

region in the Bronze Age, in particular, then poorly known. Prof. Mellink was keen that Marie-Henriette

Carre, a former undergraduate student of hers and participant at her

excavations at Karataş-Semayük, Elmalı, join the prehistoric team. Marie-Henriette was a graduate student in Near

Eastern archaeology at Yale. I was a graduate student in Classical Archaeology

at the University of Pennsylvania and was taking a course with Prof. Mellink. Moreover, Marie-Henriette and I were

dating. So we proposed that we both come

to Aphrodisias for the summer excavation season.

(Kenan Erim. www.aphrodisias.com)

Kenan Erim, who lived

in Princeton, came to Bryn Mawr for a meeting with the three of us. He was very formal, strikingly so for someone

who didn’t seem to be very old (in fact he was only 42), spoke with a British

accent, and addressed his comments entirely to Prof. Mellink. His speech struck us as a bit odd -- “My dear

Machteld” was a favorite phrase, archaic and quaint to a young American ear –

and he was eager to tell her of the injustices done to him. Rivals, such as George Hanfmann, professor at

Harvard and the director of excavations at Sardis (who had begun his project in

1958), had much more success in raising funds, even though Aphrodisias had

yielded far more spectacular finds.

We left the meeting

with conflicting thoughts. Prof. Erim didn’t

appeal as someone we were keen to work with. On the other hand, the site was

enticing. Surely the personality of the director couldn’t spoil the experience,

I thought. Marie-Henriette hesitated. I, who had as yet not worked at a big

excavation project and who had never been to Turkey, was eager to say yes. The

opportunity seemed too good to pass up.

And Prof. Mellink was in favor, too.

So we went ahead with our application and were accepted.

We arrived at the site

in June, 1972, a week before the excavations were to begin. On the way, while

waiting in the old İzmir bus station for the bus to Aphrodisias, we decided to

get married. So we arrived in a state of great joy. Kenan Erim was already

there and we fitted into his routine. At dinner, he sat at the head of a long

table in a semi-outdoor dining area, roofed, the sides protected against

insects with netting. We sat next to him, and we spoke French together. Marie-Henriette

had been raised speaking French, thanks to her father, a professor of French,

and her French mother, also a professor of French. My French, learned in

school, was passable. As for Prof. Erim, he had grown up in Geneva, where his

father worked for the League of Nations. After World War II, when his father

was appointed to the United Nations, he attended New York University; he

obtained his PhD at Princeton. He had never lived in Turkey, in fact, at least

not for extended periods of time. As a result, he felt alienated from Turkey, at

least from the Republic. Indeed, he

could trace his ancestry back through the Ottoman Empire to Byzantine

times. I am not Turkish, he would say; I

am Ottoman. My Turkish was non-existent at the time, so I couldn’t judge, or

even think to ask, to what degree his Turkish was tinged with pre-Republican

(pre-language reform) vocabulary and grammar. But with his British accent, he

hadn’t integrated into American society either, despite having lived there for

many years. Yet he felt that as a Turk he was looked down upon in America. He

didn’t really belong in one place or another, and this was clearly a source of

discomfort.

The excavation house

was located inside a walled compound. An attractive, traditional two-storied

village house was the main residence. A staircase led up to an open veranda on

the upper floor. Prof. Erim had his room to one side. I was housed in one of

the rooms at the rear, as were the other single men and older women. Marie-Henriette,

and all unmarried younger women, were given rooms in a separate building

behind. This annex was locked at night: hanky-panky was to be prevented at all

costs.

Cocktails were served on the veranda at 7:00 pm. Prof.

Erim had a record player. He would play records at cocktail hour, and sometimes

after dinner. He was very fond of certain music, which would correspond, we

would learn, to his moods. Italian movie soundtracks from the 1950s were

favorites (as a graduate student at Princeton, he had taken part in the

department’s excavations at Morgantina, on Sicily): comfort music, indicators

of a good mood. We also heard Zarah Leander, a Swedish singer with a deep voice

much loved by Germans in the Nazi period. Dinner was served at 8:00 pm, which is

late for an archaeological excavation at which work typically begins early in

the morning. The food was very good. But dinner would be served tepid, never

hot, for the cooks had prepared everything much earlier. One outstanding

dessert was a mountain of meringues with chocolate sauce, “the king of Sweden’s

favorite dessert,” we were told. It was

spectacular, it was extravagant . . . among ourselves we staff members called it

“the giant pimple.”

The site was yielding great amounts of high

quality Roman sculpture, which would be kept in the compound. Newly found

sculptures – stone heads of Romans – would be placed on the dining table in

front of Prof. Erim, for his contemplation. They were his trusted friends.

(Photo, dated 1971, found on Instagram: #kenanerim)

In the week that

followed our arrival, the rest of the staff members trickled in. Lütfi Bey was

the government representative. A young man, speaking no English or French, and

with the innate respect for authority that characterizes Turkish society, he

duly deferred to Prof. Erim. Most staff members were graduate students in

archaeology in American universities, like us: John Pollini and his wife,

Phyllis; Phil Stanley; Ron Marchese; Barbara Burrell; Barbara Bohen; Mark

Lesky; Patty Gerstenblith. Several would go on to distinguished careers. A few

specialists arrived, too: Barbara Kadish; Karen Flinn; Fred Lauritsen (a

classical numismatist). Some were newcomers, others had worked at Aphrodisias

in previous summers. All took places at the dining table next to us and on down

the table. But no one presumed to sit next to Prof. Erim, apart from Lütfi Bey.

We, as newcomers, wondered whether or not the seating arrangements were

pre-assigned. We continued to sit next to him, and to speak French – both facts

which, we would later learn, caused suspicion among certain American staff

members. Were we collaborators, telling tales on the others? Such divisions

were encouraged. Prof. Erim would tell us, in French, his negative opinions

about the table manners of others: “So-and-so is eating olives with his

fingers!” We went along, not protesting such remarks, and diligently ate our olives

with our forks, our peaches with knife and fork (my Californian habit was to

hold a peach in my hand and eat it unpeeled), doing our best to conform to his

standards of etiquette.

After a week the

excavations got under way. The work schedule was a traditional one: 7:00 am –

12:00 pm; a lengthy break for lunch and a siesta; then back in the field from

3:00-6:00 pm, six days each week. The first morning opened with a traditional

animal sacrifice for good luck, with a stew cooked and served to all the

workmen. To fend off criticism of maintaining such a custom, Prof. Erim

indicated he wasn’t in favor, but for the workmen it was essential.

Marie-Henriette and I

were assigned to trenches on the slopes of the Acropolis mound. This artificial

hill, made up of the remnants of prehistoric settlements, was cut away on one

side in the first century BC for the installation of a theater, which had been

excavated in the 1960s.

(Air view of central Aphrodisias. Roman theater partially in view, lower right. Our trenches were just to the left, behind the theater seating, lower center).

(Photo: Aphrodisias Excavations: Aphrodisias.classics.ox.ac.uk)

The aim of our explorations was to find evidence for

pre-Roman Aphrodisias. Jacques Bordaz, a professor at Columbia, had initiated

the research into prehistoric Aphrodisias, at the site and in the vicinity. In

1967, exploration of these early settlements was assigned to Barbara Kadish, a

50-ish New Yorker married to an artist, Reuben Kadish. Barbara was a warm,

friendly person, fully committed to this research. The prehistoric (pre-Roman)

investigations consisted of these trenches on the Acropolis hill, but also work

at an outlying site, called Pekmez, where she worked with Karen Flinn. She

spent little time with us, and Prof. Erim himself never came by to comment on

our excavation techniques or our finds (his interests were strictly Roman). We

worked together with Ron Marchese and Patty Gerstenblith, graduate students in

archaeology at NYU and Harvard. A small group of workmen were assigned to us;

they did the manual labor, with picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows.

Bronze Age team, Aphrodisias 1972

Standing, left to right: Karen Flinn, Barbara Kadish, three workmen, Mark Lesky, workman, Charles Gates, workman, Marie-Henriette Carre, Ron Marchese, workman. Seated/crouching, left to right: Patty Gerstenblith, six workmen

I remember being left to my own devices. Although

I dutifully followed the instructions given to me, because I had had very

little experience in field archaeology, I really didn’t know what I was doing:

how to make decisions about how to organize the digging, what to look for, and

how to record our activities. I kept a notebook, but I have not seen it since,

so I have no idea if my records made sense. But my time at Aphrodisias turned

out to be so short, only two weeks in the trenches before the storm broke, I

shouldn’t be too hard on myself. Had I

stayed the entire summer, no doubt a method would have been established and I

would have felt positive about what I had learned.

The storm broke after

our third week, after two weeks of excavating. On Saturday, the weekly day off,

students and senior staff members were expected to leave the dig house and go

on an edifying excursion. On this particular Saturday, a bus was arranged to

take us to visit Miletus and Didyma, major Greco-Roman sites on the Aegean

coast. But it was the day off, and we wanted some respite from archaeology,

too. We stopped for a few hours in Kuşadası, the main coastal resort town in

the area, to do some shopping and just walk around.

When we returned to

Aphrodisias, the bus driver reported the change in plan. Prof. Erim was furious.

At dinner he exploded. We weren’t serious! How dare we not spend all our time

in the educational activity that had been planned? Barbara Kadish responded in

kind. It was our day off; why couldn’t we decide how to spend it? The two were

shouting at each other. Barbara was at least ten years older than Prof. Erim,

and her arguments made sense. Why should

he control us as if we were schoolchildren? Finally Prof. Erim said to Barbara,

“Get out!”

She said, “Do you mean for good, Kenan?”

“Just go to your room,” he said, waving her off.

The rest of us were stunned. But what could we say? The next days were

tense. Prof. Erim was clearly mortified because he had lost control of himself

in public. He had lost face, and Barbara Kadish was responsible. Peace was not

made, though. Prof. Erim said nothing to defuse the dispute. Barbara refused to

appear at meals with him; she had food brought to her room. Moreover, she had a

heart condition which meant a weekly check at a clinic in Nazilli, the nearest

town. That week, the ride to Nazilli was cancelled.

Prof. Erim decided that the Bronze Age team,

Barbara and her team members, were troublemakers. We had to go.

Our work would stop; he would close down our trenches. The people

affected included Marie-Henriette and me, Karen, and Patty. Ron, one of our team, could stay, though. NYU

was counting this summer season as a course for Prof. Erim. Ron was registered

for the course; Prof. Erim could not afford to let this student go.

Prof. Erim never told us directly of his plan. He

disliked confronting people with bad news. He either exploded, as he had at

that Saturday dinner, or he related to others with formal politeness. He told

the foremen on the site that after a certain day, workmen would no longer

report for work in our Acropolis trenches.

We couldn’t leave right away, because our

passports were being processed for residence permits. The atmosphere during that week of waiting

for the passports was very strange, almost surreal. If Patty Gerstenblith dared to speak to Prof.

Erim, he would give her the back of his hand, he declared. Fellow graduate

students, even those working in the Roman period who were not being thrown out,

began to have strange dreams. In one such dream, a stone head, on the dining

table, began to mock Prof. Erim. He took a hammer and smashed it, but the

fragments danced in the air and continued to laugh at him.

During that week, two boys, the sons of a US

consular official in Istanbul, were visiting. The younger boy noted that Prof.

Erim went to a particular shower, at the end of the bank of showers we all

used. “Does Professor Erim have his own

shower?” he asked. Yes, he was told,

with a hot water heater. The rest of us

had sun-heated water. “That man is a

snob,” the boy said. We smiled.

I can’t remember clearly how I spent that last

week. We were no longer sitting next to Prof. Erim at the dining table. We

never exchanged harsh words – but we probably did not speak much at all with

him.

Eventually our passports came. It was time for us to leave. We walked out the gate. From the second floor veranda, gripping the

rail like a captain on his sinking ship, Prof. Erim shouted at Marie-Henriette,

in French, “At least you could have had the courtesy to say good-by, Miss

Carre!”

It’s true ... but why should she have? Why had

not he, the project director, made an effort to discuss, even defuse, the tense

situation he had created? The director

sets the tone on an excavation, not a 22-year-old student.

Marie-Henriette managed to say, “Thank you for

everything!” and off we went. This was the last time we ever spoke with him. He

would die in Ankara in November, 1990, in the residence of the British

ambassador and his wife, only a few months after we had taken up teaching

positions at Bilkent University.

That December, a delegation from New York

University came to Ankara to ensure that the government permit for the

Aphrodisias project would stay with NYU. James McCredie, the director of NYU’s

Institute of Fine Arts, presented, at a cocktail to which we were invited, the

heir apparent, the “veliaht” (crown prince) as the Turkish newspapers labeled

him: Bert Smith, a young specialist in Roman sculpture who had been working at

Aphrodisias, looking nervous as we all eyed him with great curiosity. He would

indeed become the new director of the Aphrodisias excavations, and has

continued as such, with great success, to the present day.

Fortunately, most field seasons are not as difficult

as our month at Aphrodisias. The following summer we would have a completely

opposite experience at Godin Tepe, in western Iran, a Bronze and Iron Age site

investigated by T. Cuyler Young, Jr. (University of Toronto). For three months we excavated in Bronze Age

levels. Prof. Young was outgoing, at ease with himself and others, and a superb

teacher of field methods. At Godin Tepe I learned how to dig – strategy,

execution of a plan, managing the workmen, and recording intentions, processes,

and results in my field notebook – the basis for my future field work in

Turkey, at Gritille and especially at Kinet Höyük. I enjoyed every moment.