· Illustrations are taken from the

internet, unless otherwise noted.

·

For an earlier publication on this

subject, see: Charles Gates, "American Archaeologists in Turkey:

Intellectual and Social Dimensions," Journal of the American Studies

Association of Turkey 4 (1996): 47-68.

Let me start with an

anniversary. Fifty years ago this

summer, I first set foot in Turkey. I

had just finished my sophomore year, my second year in college; I had changed

my major to Archaeology; and I was in Beirut, enrolled in the summer school at

the American University of Beirut. Mid-summer,

I flew to Istanbul for one week, to see what it was like. I had never before

met a Turkish person, as far as I know; I couldn’t say “evet” or “hayır;” and I

stayed in a dreadful hotel in Eminönü – I remember having to prop up the window

with a book -- but I had a wonderful week, nonetheless. I could never have imagined, though, that

Turkey would one day become my home, and that I would take my place in a long

line of Americans active in archaeological research in this country.

(Photo: author)

It is about these American

archaeologists that I would like to speak this evening. Who were they? Why did they come here? What did they accomplish? I can’t mention each and every name, but I

would like to give a sampling, to show the diverse interests and approaches

American scholars have had, and to identify some notable contributions that

American archaeologists have made to the study of the ancient cultures of this

country.

I should state here that I

will concentrate on work done within the borders of today’s Turkish Republic,

with only passing reference to research in adjacent areas once held by the

Ottoman Empire.

American

archaeologists in Turkey before World War I

The first American project was

at Assos, in northwestern

Turkey. From 1881 to 1883, Architects

Joseph Clarke and Francis Bacon conducted excavations here, on behalf of the

Archaeological Institute of America. 1881

– a date easy for us to remember, because that’s the year Atatürk was

born. The photographer for the

expedition was John Henry Haynes, whose important career in Anatolia, and

Mesopotamia, long forgotten, has been rediscovered in recent years by Robert

Ousterhout.

For a first foray into

Classical archaeology, Assos seems a surprising choice. It was a remote town that figured little in

ancient history. But the interest of

Clarke and Bacon was Greek architecture, and Assos contains an early and

unusual temple of Athena, ca. 540-520 BC, spectacularly located on a hilltop

overlooking the Aegean and the island of Lesbos/Mitilini. In a region dominated by the Ionic order of

Greek architecture, this temple is a surprise: it’s built in the Doric order;

it has sculpted metopes, also a Doric trait; but it also has a frieze above the

columns, which is relief sculpture in the Ionic manner. The finds from these years are divided

between the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Istanbul Archaeological Museum, and

the Louvre.

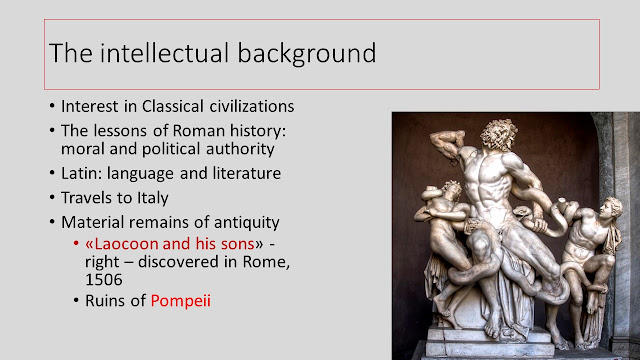

The

intellectual background

Why this choice? And why explore ancient remains at all? To answer these questions, let’s have a look

at the larger intellectual background of the 19th century.

Scientific archaeology began

in Turkey in the second half of the 19th century under the influence of

European scholarship. Coloring this was

a long-standing interest in the ancient Greeks and Romans. Classical culture had been known throughout

the Middle Ages, of course, with Latin as the liturgical language of Western

Christianity and as the common language of educated people. From the Renaissance on, Roman and indeed all

Classical culture continued to be valued for its moral and political

authority. As a result, Latin

especially, but also Greek were widely studied, even in Protestant areas, well

into the 20th century.

In addition to the

long-standing interest in ancient literature, chance finds of Roman sculpture

during the Italian Renaissance contributed to the growing fascination with the

material remains of antiquity. One thinks

especially of “Laocoon and his sons,” the dramatic Hellenistic-Roman statue

group discovered in Rome in 1506.

Collections of Classical objects were formed; and at Pompeii, organized

explorations began in 1748 and have continued to the present day.

The influence of Greek texts

reminds us of Heinrich Schliemann, a rich German businessman, who, fascinated

by the ancient stories of the Trojan War, set out to prove their veracity. Led to the site of Hisarlık by Frank Calvert,

a member of an expatriate British business family in Çanakkale, Schliemann

began excavations there in 1871 and achieved spectacular results. I wonder, can we claim him as an American

archaeologist? He had obtained US

citizenship by this point, and Calvert did serve as an honorary US consul. But this might be a bit of a stretch.

Back to our larger

picture. The Ottoman Empire controlled

lands once key provinces of ancient Greek and Roman civilization. Because of restrictions and rigors of travel,

visitors from Western Europe were few before the later 18th century. When European travellers did make the trip

and report on their findings, the impact was tremendous. Italy was long familiar to westerners, but

now the specifically Greek component of the Classical world was being revealed.

In the 19th century, European

travellers continued to describe ancient sites in Anatolia, and make drawings

of the monuments. In addition, they

often took objects away, actual examples of Classical art, whether or not

official permits were granted. Ottoman

authorities had paid scant attention to such activities. This is not surprising, for the Latin and

Greek languages and Classical cultures naturally enough did not feature in the

Islamic-oriented education of Ottoman officials or resonate in their daily

lives. Only with the quickening of

interest in European culture from the 1850s on did the Ottoman intelligentsia

develop along with Europeans a curiosity toward the antiquities of their lands.

Sultan Abdulmejid and his

son-in-law Fethi Ahmet Pasha began a collection of antiquities in 1845, the

basis for the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul. With the appointment in 1881 – again, our

fateful year of 1881 -- of Osman Hamdi Bey as director, the museum moved into a

new era of expansion and activity, culminating in the opening of the present

museum building in 1891. Laws regulating

archaeological activities were issued first in 1874, then revised in 1884. This

last set, which included a prohibition on the export of antiquities, continued

in effect with minor revisions until 1973.

To return to the exploration

of Assos: What was the immediate American

context for these excavations? In the

United States, the institutional framework for the study of archaeology,

Classical and other, was being put into place at this very time. The Archeological Institute of America was

founded in 1879. Although its interests

were global, the Mediterranean basin would eventually become its focus. The two major research centers for Classical

Studies were soon to come: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens

(founded in 1881) and the “American School of Classical Studies” in Rome, in

1895, eventually to become the American Academy in Rome.

Note that Istanbul, although a

major historical center in the larger southeastern European region, was not yet

an important center for research into Classical or any other branch of

antiquity.

Other Old World civilizations

well represented within the territory of the Ottoman Empire were also much

studied, by Americans as well as others. Texts were always the key, just as

Greek and Latin texts had fueled interest in Classical cultures. The Bible stimulated archaeological exploration

in Palestine. Indeed, in 1899, the AIA

founded the American School of Oriental Study and Research in Palestine,

eventually to become the American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR). In Iraq and Syria, the decipherment, in the

mid to late 19th century, of Akkadian and Sumerian allowed a deeper

understanding of Mesopotamian cultures. Although

the the rediscovery of the Hittites grew out of an interest in the Biblical

world and the Ancient Near East, French and then German explorations at

Boğazköy/ Hattusa, the Hittite capital, were given new impetus by the

decipherment of the Hittite language in the early 20th century. And in Egypt, whose ancient writing system

was deciphered in the early 19th century, the study of texts and well-preserved

architecture and art was well advanced by World War I. Each of these areas would become a

specialized field of study.

After Assos, the next American

project in today’s Turkey was at Sardis,

where Howard Crosby Butler of Princeton University, directed excavations from

1910-1914, at the invitation of Osman Hamdi Bey. Butler, an architectural historian, had

already investigated Late Roman sites in Syria.

Although Sardis was a major city in the Roman Empire, its earlier history

was well known from Herodotus and other ancient writers. During the Iron Age Sardis was the capital of

the Lydian kingdom. The Lydians were a

native Anatolian people, even if much influenced by their Greek neighbors and

subjects. Butler’s aim was to get

information about the contribution of such non-Greek Near Eastern peoples to

Classical art and architecture. But as

it so happened, his work focused on exposing the huge Hellenistic-Roman Temple

of Artemis, as well as over 1000 tombs in nearby cliffs. The project was stopped by the outbreak of

World War I. Butler returned briefly in

1922, but died later that year. American

research at Sardis would not resume until 1958.

Between

the two World Wars

After World War I, new

excavations on Greco-Roman sites were begun by American teams: short-lived

projects at Colophon, in the Aegean coastal territory briefly occupied by

Greece, and at Pisidian Antioch, near Yalvaç; and a major campaign in the 1930s

at Antioch-on-the-Orontes (today’s Antakya), then in the French-occupied Sanjak

of Alexandretta, under the sponsorship of Princeton University.

The aim of this last project was

to reveal the city of Antioch, one of the four great cities of the Roman

Empire, from Hellenistic to medieval times.

This goal was believed possible because in the 1930s, ancient Antioch

was overlain by only a small modern city – unlike Rome or Constantinople/Istanbul. It quickly became clear that very deep silt

deposits from the Orontes River concealed the ancient city. Quick and satisfying results were thus

difficult to obtain. In the end, after the villas of suburban Daphne began

yielding one fine mosaic after another, the excavators made a virtue of

necessity and, giving up on the vast deep soundings, concentrated on the

mosaics. Some of these spectacular

mosaics are on display in the Antakya Archaeological Museum, in the Louvre, and,

in the United States, in museums at Princeton, Baltimore, and Worcester, MA.

The inter-war period was

particularly notable, though, for the American entry into the prehistoric and

pre-Classical field.

At Troy, Carl Blegen of the

University of Cincinnati, taking a break from his prolific research in Greece,

excavated from 1932 to 1938, supplementing the earlier findings of Schliemann

and his assistant and successor, Wilhelm Dörpfeld. The Library at the American School of

Classical Studies at Athens and one of the main libraries at the University of

Cincinnati are named in his honor.

The Oriental Institute of the

University of Chicago was founded in 1919 – yes, this great research center is

celebrating its centennial this year – founded by the Egyptologist James

Breasted with financing from John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to promote research into

the cultures of the Ancient Near East and Egypt. The Institute sponsored teams that conducted

important surveys in central Anatolia and excavations at Alişar Höyük (near Yozgat)

under the direction of a German archaeologist and adventurer, Hans Henning von

der Osten, and in the Amuq Plain, northeast of Antakya, by Robert

Braidwood.

In 1935, Hetty Goldman, soon

to be appointed professor at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, began

excavations at Gözlü Kule, the prehistoric settlement at Tarsus. The results proved seminal for the

understanding of Bronze and Iron Age cultures in Anatolia. Goldman, first at Colophon in 1922, then at

Tarsus, was the first American woman to direct an archaeological excavation in

Turkey. Much credit must to to Bryn

Mawr, Goldman’s alma mater, the small but distinguished women’s college whose

perennially strong programs in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology have

encouraged many to enter the field. The

Tarsus excavations were carried out from 1935 to 1938, with two post-war

seasons in 1947 and 1948. As we shall

see, those post-war seasons included staff members who would go on to direct

their own excavation projects in the 1950s and beyond.

By 1939, German archaeological

research in Turkey was active and influential.

In 1929, the German Archaeological Institute had established a center in

Istanbul to further its research projects.

The large projects at Pergamon, Miletos, and Boğazköy/Hattusha – to

which we might add (in the German-speaking world) the Austrian excavations at

Ephesus, which began in 1895 -- had already uncovered much and published

well. In addition, Istanbul and Ankara

Universities were organized on German models.

The relation with Germany had

another dimension as well, one that would affect the United States. In 1933, the Nazi regime expelled Jewish

academics. Many of these scholars,

together with non-Jewish dissidents, would be welcomed in Turkey and given

university appointments in Istanbul and Ankara.

Among them was Hittitologist Hans Güterbock, who joined the staff of

Ankara University. Like many, he began

by lecturing in German with translation into Turkish, but eventually was able

to give the lectures himself in Turkish.

After the war, this community dispersed, some leaving voluntarily,

others the victims of a nationalist reaction in 1948 that led to the dismissal

of these foreign professors. Several

eventually found positions in the United States. Güterbock, for example, after a short stint

in Sweden, was hired by the Oriental Institute.

He would eventually serve as ARIT president from 1969 to 1977, and remained

a dedicated board member for many years beyond.

A lot of thanks for your own effort on this website. My aunt delights in getting into investigation and it is easy to understand why. Almost all know all relating to the powerful mode you provide informative tips and tricks via your web blog and cause contribution from other people on that subject matter and our child is certainly being taught a great deal. Take advantage of the remaining portion of the year. You are carrying out a wonderful job.

ReplyDeleteafrican maxi skirts for sale